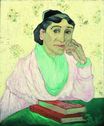

Винсент Ван Гог - Арлезианка. Мадам Жино 1890

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Арлезианка. Мадам Жино 1890

60x50см холст/масло

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna

<< Previous G a l l e r y Next >>

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

The subject, Marie Jullian (or Julien), was born in Arles June 8, 1848 and died there August 2, 1911. She married Joseph-Michel Ginoux in 1866 and together they ran the Café de la Gare, 30 Place Lamartine, where Van Gogh lodged from May to mid-September 1888. He had the Yellow House in Arles furnished to settle there.

Evidently until this time, Van Gogh's relations to M. and Mme. Ginoux had remained more or less commercial (the café is the subject of The Night Café), but Gauguin's arrival in Arles altered the situation. His courtship charmed the lady, then about 40 years of age, and in the first few days of November 1888 (November 1, or more probably November 2) Madame Ginoux agreed to have a portrait session for Paul Gauguin, and his friend Van Gogh. Within an hour, Gauguin produced a charcoal drawing while Vincent produced a full-scale painting, "knocked off in one hour".

While in the asylum at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh painted another five portraits of Madame Ginoux, based on Gauguin's charcoal drawing of November 1888. Of these, one was intended for Gauguin, one for his brother Theo, one for himself and one for Madame Ginoux. The provenance of the version in the Kröller-Müller Museum is not known in detail, but the painting is known to have been previously owned by Albert Aurier, an early champion of Vincent's paintings. The version intended for Madame Ginoux was lost and has not been recovered. This is the version Vincent was delivering to Madame Ginoux in Arles when he suffered his relapse on February 22, 1890. In an unfinished letter to Gauguin that was never sent, Vincent remarked that working on her portrait cost him another month of illness. Gauguin's version was the one with a pink background, currently in the São Paulo Museum of Art. Gauguin was enthusiastic about the portrait, writing:"I’ve seen the canvas of Madame Ginoux. Very fine and very curious, I like it better than my drawing. Despite your ailing state you have never worked with so much balance while conserving the sensation and the interior warmth needed for a work of art, precisely in an era when art is a business regulated in advance by cold calculations."

In a letter to his sister Wil, dated 5 June 1890, Vincent set out his philosophy for doing portraits: "I should like to do portraits which will appear as revelations to people in a hundred years' time. In other words I am not trying to achieve this by photographic likeness but by rendering our impassioned expressions, by using our modern knowledge and appreciation of colour as a means of rendering and exalting character ... The portrait of the Arlésienne has a colourless and matt flesh tone, the eyes are calm and very simple, the clothing is black, the background pink, and she is leaning on a green table with green books. But in the copy that Theo has, the clothing is pink, the background yellowy-white, and the front of the open bodice is muslin in a white that merges into green. Among all these light colours, only the hair, the eyelashes and the eyes form black patches."